The Nengo System, Reading the Japanese Calendar

When you come to Japan and go to register the city office, or with a number of services, you will notice that the space for the year you were born might say something like Showa [昭和], Heisei [平成]and sometimes even Taisho [大正]. These unusual labels are regnal eras, or nengo [年号], and are very common throughout Japan. In fact Japan is one of the few countries in the world that still uses regnal eras in day to day life. Although the standard Gregorian calendar is becoming more and more common, knowing about the nengo is still an important part of life in Japan. 2019 is especially exciting because in May, a new emperor will take the crown and a whole new nengo will begin.

What is Nengo?

The first thing people need to keep find confusing about the nengo system is that the name of a nengo and the name of a period or era are totally different things. For example, the Edo Period, which spans from 1603 to 1868, but there isn’t an Edo nengo. Also, sometimes a major event will be the name of nengo, but not a period. For example, when the Onin War broke out, the nengo was Onin, but there is no Onin period. As a matter of convenience, after the reign of Emperor Meiji, each nengo became a period.

So, what exactly is a nengo? A nengo is the name for the era governed by a specific emperor. For example, Emperor Showa began his rule on December 12th, 1925. Therefore the first year of the Showa nengo also began on that date and ended on December 31st, 1925. In total, the Showa nengo lasted for 64 years. While today you will likely only see Heisei, Showa, Taisho and perhaps Meiji, but there are as many as 247 nengo to date. Additionally, the name of a nengo usually consist of two kanji, however in ancient times there were some that had four kanji.

Year 1

The first one began in 645, just after Japan created the Taika Reforms, ergo creating a strong centralized political government. However, this system did not originate in Japan. The Chinese had their own nengo dating back to roughly 140 BCE. While the ancient Korean Kingdoms adopted the same system as China, Japan decided to modify the Chinese system.

Today, there is basically only one nengo for each emperor, but this was not always the case. In ancient Japan, emperors frequently changed nengo after major events or disasters. For example, just before the reign of Emperor Meiji was Emperor Komei, who had 6 different nengo. Due perhaps in part of this excessiveness, Meiji decreed that there should be only one nengo per an emperor’s reign.

Know Your Year

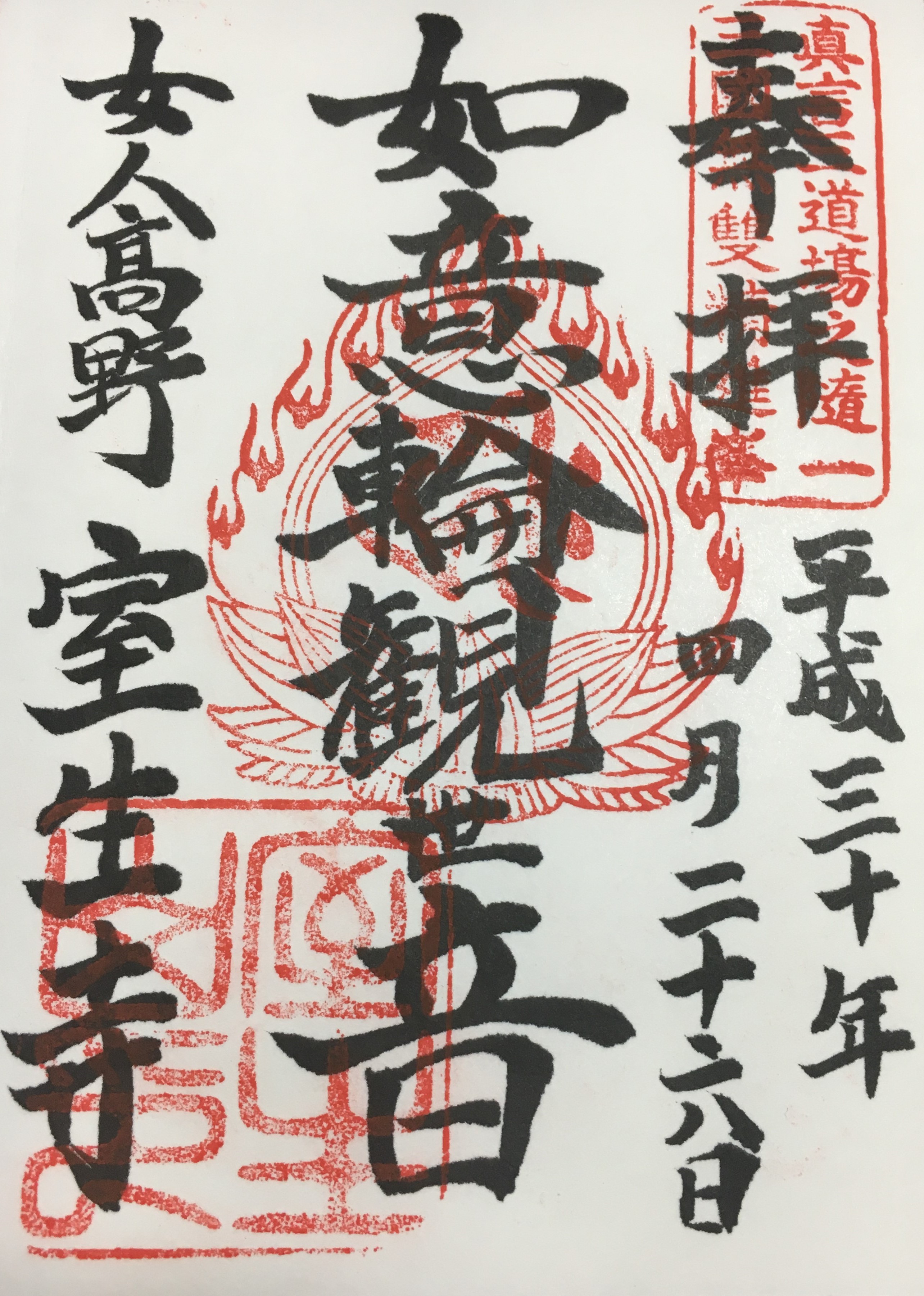

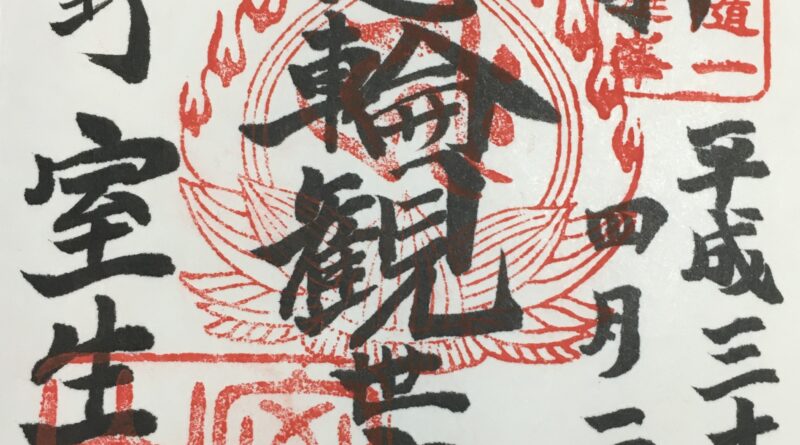

So, here is the chart you can figure out your year. Be careful sometimes there can be sudden changes in the middle of a year.

As we mentioned, in May 2019, Japan will crown a new emperor, meaning there is going to be a new nengo. Previously, emperor’s almost exclusively decided the name of a new year. However, today it is not the emperor, but the current prime minister and a group of scholars who come up with this name. Moreover, they usually draw inspiration from a collection of old Chinese books called The Four Books and Five Classics.

Other Calendar Systems

In addition to this calendar system, Japan once used several other year systems.

Jikkan Jyuunishi System

In ancient Japan, dates and years were represented by combining two theories: jikkan [十干] and jyuunishi [十二支]. As you most likely know, the jyuunishi are twelve animals that represent direction, times, and dates. These twelve animals are:

子 “mouse” 丑 “cow” 寅 “tiger” 卯 “rabbit” 辰 “tiger” 巳 “snake”

午 “horse” 未 “sheep” 猿 “monkey” 酉 “chicken” 戌 “dog” 亥 “boar”

The jyuunishi came to Japan from China, and are still common in Japan today. New Year’s is certainly the most obvious example of when Japanese society still uses the Jyuunishi, as it is common to have a drawing of the coming year’s animal on a nengajo, or New Year’s card.

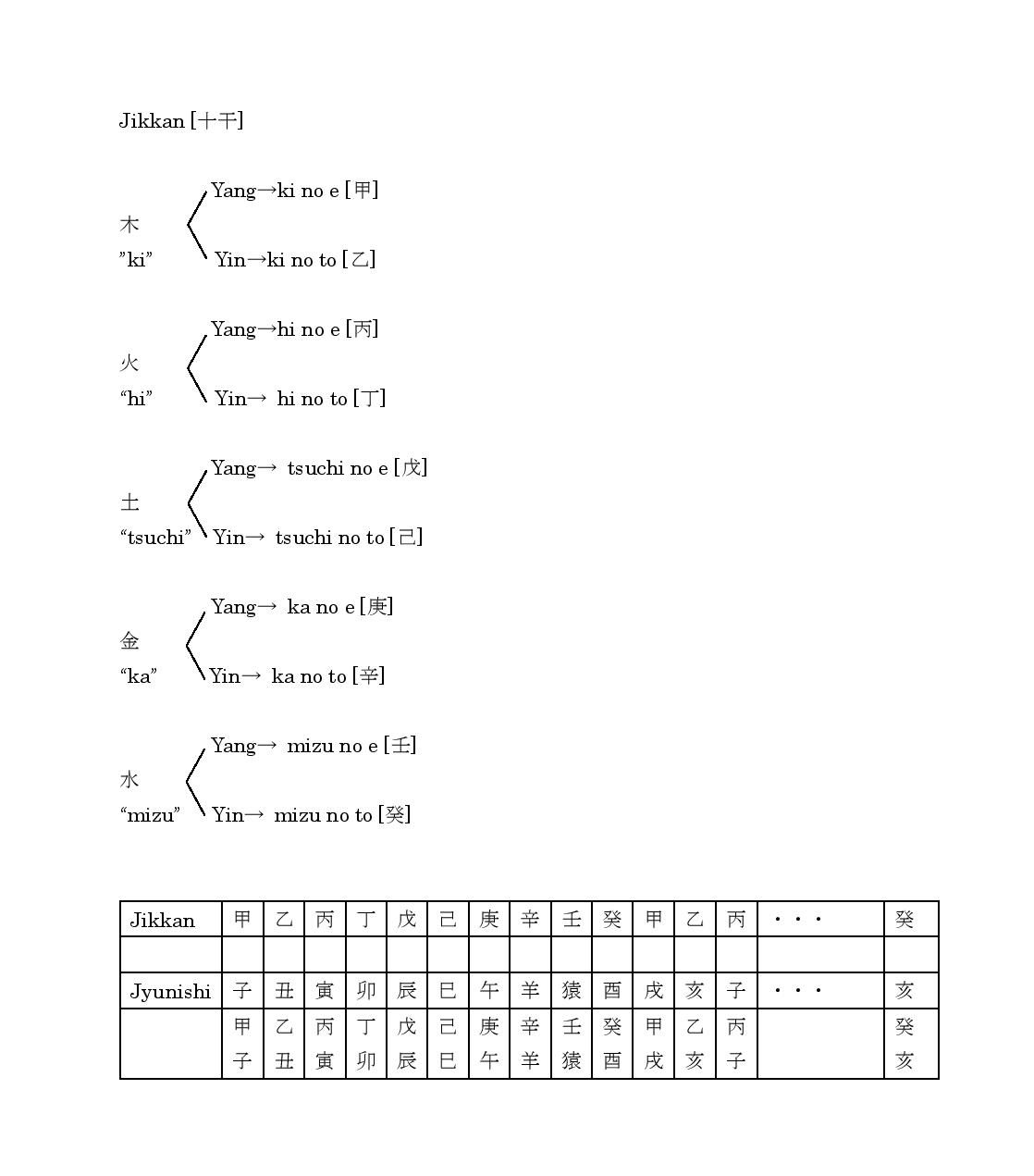

Jikkan, which was also introduced from China, is a combination of the five Chinese elements [五行説] and the principles of yin-yang [陰陽]. Essentially each of these elements, namely fire [火], water [水], earth [土], metal [金], and wood [木] were further broken down by the principles of yin and yang. When this concept moved from China to Japan, yin was translated to e [兄], or“big brother”, and yang to to [弟], little brother.

The result is something like this:

There are a total of 60 different combinations of jikkan and jyuunishi. Though it may sound extremely complicated, this traditional time representation was used in very familiar place: the Koushien Baseball Stadium[甲子園]. 甲子 stands for ki no e [甲]+ ne [子], pronounced “koushi”, because Koushien Baseball Stadium was built in a Koshi Year.

Kouki (Imperial Year System)

From the Meiji Period and throughout WWII, Japan refused to use the Gregorian calendar. Rather, they used imperial year system, or kouki. The first year of the kouki system is 660 A.D. with the coronation of Japan’s mythical first emperor, Emperor Jinmu.

However, after WWII, Japan retired the kouki system. Today, only a few very traditional shrines continue to use this system, as well as some extreme right wing activists.

While the nengo system might seem strange or even archaic to non-natives of Japan, it doesn’t seem to be going anywhere any time soon. Steadfast in its traditions, Japan will likely continue to count rengal years until the end of the Imperial family. Hopefully understanding the origins of this unusual calendar system will make it seem less perplexing.

Leave a Reply