Koshin Mairi at Shitennoji : A Rare Japanese Tradition Found In Osaka

Though Japan has been able to preserve a great number of its ancient traditions, there are still some traditions that are no longer common, or even disappearing. A prime example is koshin. Held on a special “koshin day” this festival back to ancient times and was once one of the most widely practiced and important ceremonies in Japan.

What is a “Koshin Day?”

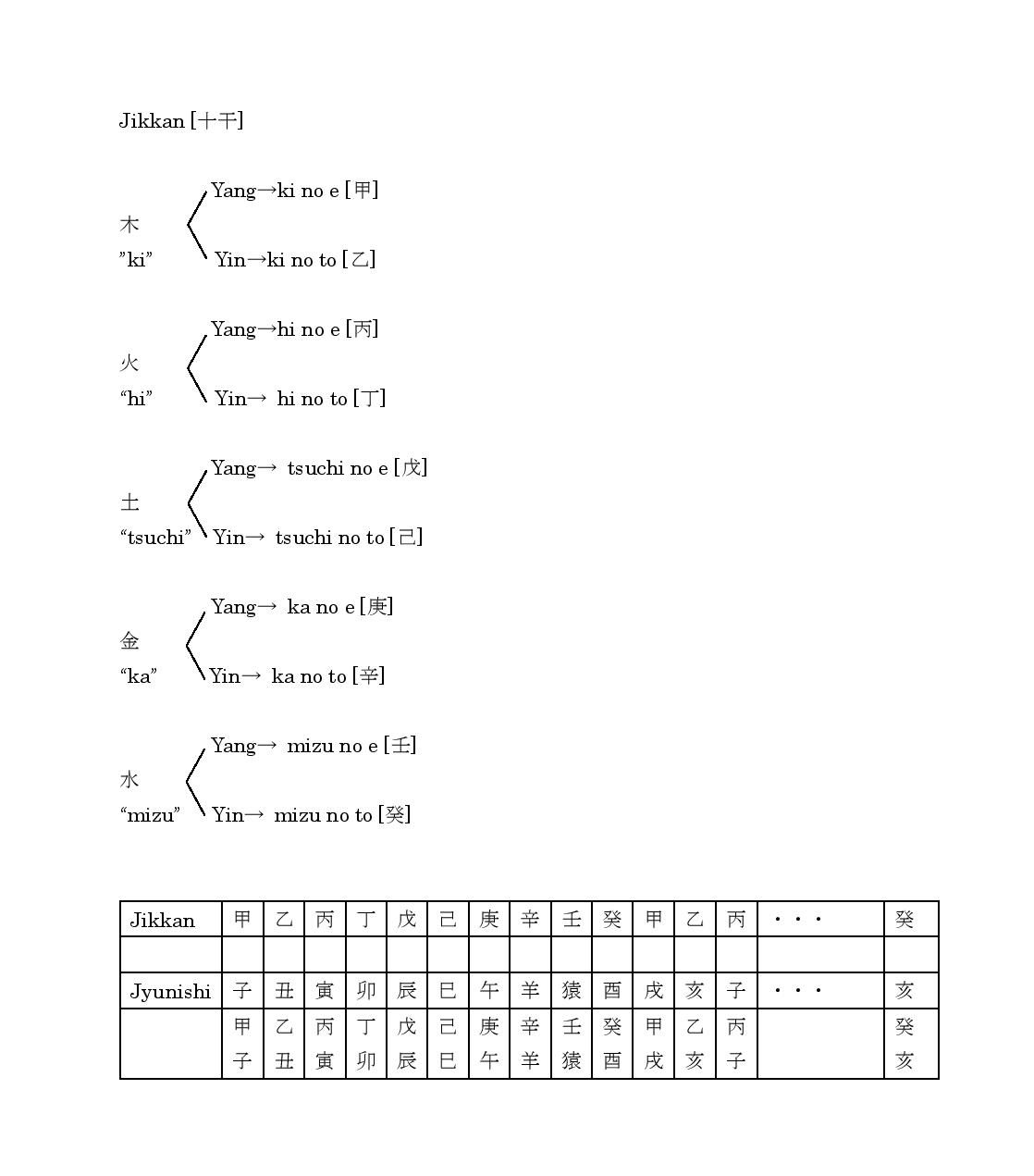

Before talking about what koshin mairi, you have to know when is “koshin day”. In order to know when koshin day is you have to be familiar with the Jikkan Jyuunishi calendar system, a system once used in ancient Japan to keep track of the year.

The Jikkan Jyunishi system starts from kinoe- ne [甲子] kinoto-ushi [乙丑], hinoe-tora[丙寅], hinoto-u [丁卯] and the 57th is konoe-saru [庚申], or koshin. There are 60 patters in the Jikkan Jyunishi system.

The quickest way is to find out when the next koshin day is to visit Shitenno-ji’s website and check the schedule of koshin day.

The Origins of Koshin Mairi

According to Taoism, it was believed that there are three worms, sanshinomushi, that live in people’s stomachs.

On a koshin day when the body goes to sleep these three parasitic worms escape from the body and tell the gods in heaven what kind of sins the person has committed. The gods then punish the person, by shortening their lives according to the number, as well as the severity of their sins. Since these bugs can only escape when a person goes to sleep, people simply did not sleep on this day.

This rather funny custom came to Japan from China around the Heian Period. Like the Chinese aristocrats, Japanese aristocrats stayed up by playing music and reading poems to keep the sanshinomushi from escaping. This practice was called koshin machi. By the Edo Period, commoners had started to practice koshin machi too.

The commoners soon realized, however, that it was much easier to stay up with their friends rather than by themselves. As you can imagine, people would drink and chat the entire night and it became a sort of official party day.

Despite these festivities, eventually people thought just staying up was not enough. Originally, people worshiped Shomen-Kongo to eradicate illnesses, but over time they started believing he could help prevent those nasty sanshimomushi from getting out too.

Shomen-kogo’s apostles were believed to be a monkey and they help prevent gods from knowing one’s sins. That’s how “mizaru (Don’t see), iwazaru (don’t say), and kikazaru (don’t hear)” originated.

Koshin-do Temple Grounds

Koshin-do is affiliated with Osaka’s famous Shitennoji, and is 10 minutes away from Shitennoji’s main temple. Shitennoji Koshin-do enshrines Shomen-Kongo, and was originally one of three of the most prominent Koshin-do temples in Japan.

Koshin Mairi festivals take place on the day before koshin, as well as the actual day itself.

We went before noon on week day, so there weren’t that many people.

The main temple burned down during the Osaka Air Raids of WWII. This may come as total surprise, but the current building serving as the main temple was a rest area during World Expo 1970.

Monkeys the apostles of Shomen-Kongo and you can find them dotted throughout this small temple.

A traditional ritual that takes place at the temple on this day is saru kaji. This ritual involves a large wooden monkey on a person’s back while someone from the temple recites a special chant meant to help the sanshinomushi at bay.

Once you enter the temple ground, you will notice this konyaku stand. For some reason those pesky little worms in your stomach hate konyaku, so it is traditional to eat konyaku during this time. It is customary to eat the konyaku facing north, i.e the direction of the hondo, in complete silence.

Festivals like these are few and far between these days. These ceremonies are predominately in very rural areas in Japan and often function as a neighborhood get-together, but is still sadly dying out. If you get a change to witness, or even participate, in this now rare part of Japanese culture, I think you should. It is special to be able to find opportunities a thousand year old tradition without even having to leave the city!

Leave a Reply