Sugawara no Michizane, Japan’s Most Famous Scholar

In the Shinto religion, there are literally thousands and thousands of gods; but everyone has favorites. Easily one of the most popular, and certainly well-known Tenmangu, the god of knowledge. There are more than 10,000 Tenmangu shrines throughout Japan and every year just many students swarm those shrines to pray for success during their university entrance exams. However, while these shrines represent study today, at one time they instead aimed to sooth the vengeful spirit of the scholar Sugawara no Michizane [菅原道真].

The Life of Sugawara no Michizane

In order to understand the god Tenmangu, let us talk about the man, Sugawara no Michizane.

A Born Scholar

Born into the prestigious Sugawara family in 845, Michizane had some big shoes to fill. Michizane’s father for example, lectured on Chinese poetry and was a monjo hanakase [文章博士], one of the highest ranks for a scholar at the time. Under the guidance of his father, Michizane studied very hard, and soon his natural genius emerged. He started reading poetry when he was only 5 and could read Chinese poetry by the time he was 11. At 18, he passed the national exam necessary exam to become a government official. His diligent nature also helped him to pass many difficult exams for the first try. By the time he was just 33, Michizane acquired the rank of monjo hakase, just like his father.

The Ako Controversy

Soon after he became monjo kakase, Michizane was dispatched to govern the Sanuki Province. While he did a great job governing Sanuki, serious problems were brewing back in Kyoto. At that time, Emperor Uda appointed Fujiwara no Mototsune as his Chief Imperial Advisor, or kanpaku [関白]. Shortly after, however, the emperor issued an edit stating that the position of kanpaku was the same as an ako [阿衡] in the Chinese courts. This edit greatly infuriated Mototsune because an ako is a position without any real authority. Enraged, Mototsune used his family’s influence to essential bring politics in the capital to a standstill. Feeling at a loss, the emperor called upon Michizane to resolve the issue. Michizane came all the way to Kyoto and persuaded the Uda to re-instate Motsune as kanpaku and to strike the term ako from his edicts.

Life in Kyoto

After his handling of the Ako Controversy, Emperor Uda greatly respected Michizane and gave him a position as one of his personal secretaries. Of course, with Michizane’s sharp intellect, he was quickly promoted to Minister of the Right.

Not long after he obtained this key government position, the emperor appointed Michizane to study abroad in China. However, China was in the middle of a vicious war and a number of Japanese monks and scholars had already perished overseas. Using his skills of argumentation, he convinced Emperor Uda there was no merit for him to risk his life in China. His argument was so good that the emperor halted all study abroad efforts to China.

Not only did this mean Michizane could stay comfortably in his position, but it also gave Japan the opportunity to cultivate its own art forms, theories, and identity. For example, the Japanese developed hiragana around this time.

Banishment

Luckily for Michizane, Fujiwara no Mototsune died during his rise to power. This left almost no political rivals for Michizane, as Mototsune’s and his son, Fujiwara no Tokihira was still very young. Because Michizane got along with Emperor Uda, they arranged to betroth Michizane’s daughter Uda’s grandson son, Tokiyo, upon birth. However, this close relationship between Uda and Michizane upset the Fujiwara, who for many generations betrothed their daughters to Japan’s crown princes, thereby ensuring the clan’s political power.

Eventually, Uda abdicated his throne and Emperor Daigo came to power. While Michizane still held a lot of power under Emperor Daigo, it was certainly less than it was during the reign of Emperor Uda. This gave Fujiwara no Tokihira an opportunity to finally drive a wedge between Michizane and the emperor. Tokihara told Emperor Daigo that Michizane was secretly trying to dethrone him in order to allow Tokiyo to become emperor. Completely taken in by this lie, Emperor Daigo demoted Michizane and banished him to Daizaifu in Kyushu. Emperor Uda tried to defend Michizane, but alas his efforts were in vain. Deeply disheartened, Michizane left Kyoto.

Michizane in Dazaifu

At the time of his banishment, Dazaifu was little more than strategic military point to protect Japan from China and Korea. Michizane was clearly not suited for his new position, and rather resented it. The house he was provided was just a ramshackle building and barely made enough to feed himself. Every day, he longed to return to his beloved Kyoto. Sadly, during his time in Dazaifu his young son died only making him more morose. Shortly after his son’s death Michizane passed away on Feburary 25 in 903 at the age of 59. Only two years had passed from the time he moved to Dazaifu to the time of death.

They buried Michizane in Anraku-ji Temple, or what is today Dazaifu Tenmangu Shrine, one of the most popular and famous Tenmangu shrines.

Michizane’s Revenge

Michizane’s story, however, didn’t end with his death. Soon after Michizane passed away, there were many natural disasters in Kyoto such as fires and earthquakes. In addition, not only did Fujiwara no Tokihira die when he was only 39. Surely, this was the work of Michizane’s vengeful spirit. In an attempt to appease his ghost, officials officially pardoned Michizane restored his title. However, disasters continued to plague the capital. Then Emperor Daigo’s son died and soon after, so did his grandson. Desperate, the government allowed Michizane’s family to come back to Kyoto.

In 930, a dark cloud settled over the palace during an important government meeting. Suddenly lightning struck the palace, setting it on fire. Many people died; some died instantly and some burned to death. Coincidentally, many of them were involved in Michizane’s demotion. However, Fujiwara no Tokihira’s brother, Tadahira, who had treated Michizane kindly during his life survived this incident unscathed.

The government determined that Michizane must in fact be the god of thunder enacting his revenge. The only way to make this havoc stop, was to enshrine him in Kyoto and humbly offer him their apologies.

From Lightening to Learning

The government decided to build Kitano Tenmangu Shrine in Kyoto, in the same location as the shrine for the god of thunder. Since Michizane was now the god of thunder, they gave him the name Tenjin, literally meaning god of the heavens.

Gradually, people began to forget the violence that led Michizane’s deification and instead, began worship him for his famous the intelligence. In the Edo Period the government set about building many schools. Often times the government built Tenmangu shrines in order to protect those school naturally strengthening the association between Tenmangu and study. In this way, Tenmangu became the god of study. It is also why examinees visit his shrines before the university exam rush.

Michizane’s Plum Tree

When it comes to Tenmangu shrines, plum trees are certainly very iconic. This is because Michizane favored plum trees, and many of his most famous poems feature them. One such example reads as follows:

「東風吹かば 匂い起こせよ 梅の花 主なしとて 春な忘れそ」

Kochi fukaba / Nioi okkoseyo / umeno hana/ aruji nashi tote/ haru na wasureso

“When the east wind blow, carry the fragrance along the wind, dear my plum tree. Do not forget to bloom just because your master is not there”

According to legend, after reading this poem, his plum tree flew to Dazaifu from Kyoto in order to be with him. For this reason, almost all Tenmangu shrines have plum trees somewhere on their shrine grounds. and some of those shrines have extensive plum gardens like Domoyo-ji Tenmangu in Osaka.

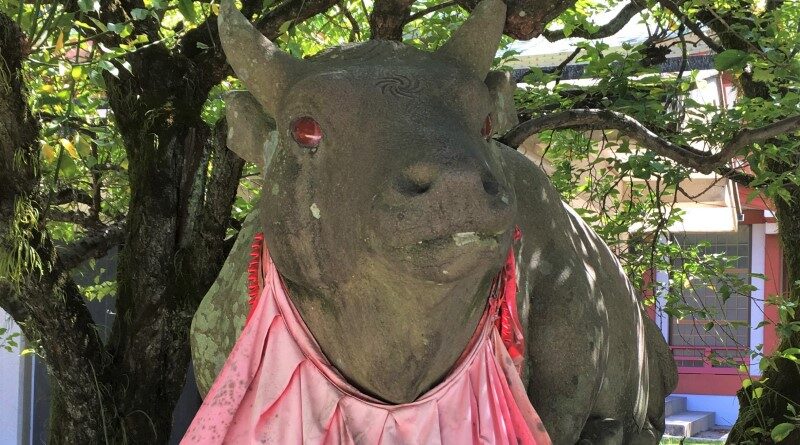

Beloved Bovine

Another important symbol in a Tenmangu shrine is the cow. There is always at least one statue of a resting cow in a Tenmangu shrine.

People are not certain of the exact reason why cows are in Tenmangu shrines. Many believe the reason is because when Michizane died, the cows of his funeral cart wouldn’t move. This is also probably why the statue of the cows in Tenmangu are often sitting down.

Leave a Reply