A Basic Guide to Shinto Shrines

Shrines obviously make up a large part of the landscape and culture of Japan. Many people, more times than not, say that one of the big attractions of visiting Japan is being able to stop by a centuries old shine. On this blog we love shrines! They are a great way to learn local history, mythology, folklore, and best of all they are usually free! However, outside of Japan, practically no one practices Shinto meaning Japan has a monopoly on Shinto shrines. This means that most people are naïve as to what exactly is in a Shinto shrine, and with so many terms and components, it is easy to become confused. So today, we are going to shed some light on these pillars of Japan with out basic guide to Shinto shrines.

What is Shinto?

Shrines are the Shinto structure that enshrines a particular god(s). While there are many different sects of Buddhism, Shinto has only two schools of thought: Kyoha Shinto and Jinja Shinto.

Branches of Shinto

When anyone says “Shinto”, more than likely they are referring to Jinja Shinto. This branch of Shinto is the largest religious group in Japan with practices dating back to the very beginning on Japanese culture. Jinja Shinto believes in a number of gods, kami, who govern the world of man and the cosmos. There is no “heaven” in the western sense, but rather a place called Yomi that houses the souls of the dead, and is a little similar to the Ancient Greek concept of Hades or Tartarus. Rather than being rewarded when you die, Jinja Shinto rewards you when you are alive. By paying homage to the gods and being respectful of their shrines, these gods might grant you wishes or perform favors to make your life easier.

Jinja Shinto is an extremely lax religion that does not have a holy book, strict rules, or even require regular attendance to religious ceremonies. This flexible nature has likely helped Jinja Shinto endure throughout the centuries.

Shinto Gods

Shrines always has at least one enshrined god, or deity. Though shrines sometimes enshrine historic figures such as Sugawara no Michizane in Tenmangu shrines or Toyotomi Hideyoshi in Hokoku shrines, many shrines enshrine the mythological gods that appear in the Kojiki and Nihon Shoki. So, naturally, reading either of these books will greatly help foster and appreciation for the shrines you intend to visit.

Sometimes, the name can give you a clue as to which god is enshrined there. For example,

Shrine names and gods

Inari → Enshrines the god Uka no Mitama [宇迦之御魂神]

Hachiman-gu → Enshrines the Hachiman gods [八幡神]

Tenmangu → Enshrines Sugawara no Michizane [菅原道真]

Visiting Shinto Shrines

Torii [鳥居]

Shinto shrines are almost always framed by a large gate called a torii. Torii basically divide the realm of gods and man, which is why a Japanese person may bow just before entering or just after visiting a shrine.

Since temple usually do not have torii, it is one of the easiest remarks you can find in distinguishing shrines from temples. Instead, often temples have a gate called sanmon, however, this generalization may not always be the case, as sometimes a torii will stand before the entrance of a temple. To complicate things even more, sometimes there might be a sanmon style gate in front of a shrine.

So, why are there elements of shrines in temples and vise versa? The answer is because for many centuries Shinto and Buddhism were not clearly divided in Japan. Even after these religions were forced to clearly differentiate themselves. This is why some torii still remain in temples or a shrine might not even a have a torii.

Komainu and Shishi [狛犬・獅子]

Near the entrance of a shrine, you will find a pair of statues on the right and left that look like dog or maybe lion. These statues always face the outside of the shrine as a means to ward off the bad spirits.

Now both statues are called casually referred to as “komainu” but if you closely you will clearly notice something; the one on the left has a horn and the other does not (though sometimes the horn can be hard to notice). The statue of the horned animal is indeed a statue of the lengendary Japanese animal known as a komainu, however, the staute on the right is what is called a shishi, which is a legendary Chinese animal. Traditionally, the mouth of the shishi often open as if it were saying “A” and the mouth of the komainu is closed as if to say “N”. The reason the shishi says “A” and the komainu says “N” is because both the Japanese and Sanskrit alphabets start and end with those same sounds.

Furthermore, not all shrines use shishi and komainu, but instead use a fox, cow, or some other animal. These animals are considered to be the apostles of the god(s) enshrined in that specific shrine.

Chozuya and Sando [手水舎・参道]

Between the komainu and shishi, you will see a path called the sando that will lead you to the main building(s) of the shine. Once you pass through the torii you are in the realm of the gods and it is believed that the center of the sando is supposed to be reserved for gods only, and that humans should walk off to the right or left.

Just before the main building of the shrine, is the chozuya. At the chozuya you are meant to purify yourself before presenting yourself before the gods, by washing the hands and mouth. Like in many other cultures, water has been viewed as a symbol of purity since ancient times.

How to Purify Yourself at the Chozuya:

- Holding ladle in your right hand, scoop up some water and wash your left hand.

- Transfer the ladle to left hand wash your right hand.

- Swithch the ladle back to the right hand and pour a little water in your left hand to wash your mouth. (You do not have to drink the water)

- Then tilt the ladle back, allowing the remaining water wash the handle of the ladle

Honden and Haiden [本殿・拝殿]

At the heart of the shrine grounds are two kinds of buildings: the honden and haiden. The honden is where main god(s) resides. Since the honden is very sacred, essentially nobody, including priests, can enter the honden. The haiden is where you pray to the gods, and is often in front of the honden.

There are even some shrines, like Omiwa Shrine, that do not have honden because the god worshiped cannot/doesn’t want to be contained in a honden, like a mountain for example.

Sanpai [参拝]

When someone goes to a shrine to pray, it is called sanpai. Once you are standing before the haiden your can pray to the god in the honden by making them an offering and performing a quick prayer ritual. While, again, there can be some variation in how this ritual is performed, generally is as follows:

How to Pray at Shinto Shrines

- Ring the bell near the collection box (sometimes there is no box)

- Put money in the collection box

- Bow twice

- Clap twice

- Close your eyes and pray

- Bow again

Sessya and Massha [摂社・末社]

As you are walking around the shrine grounds you will notice that there are many little shrines near the honden and haiden. These little shrines are called sessya and massya. Technically, sessya enshrine a deity that is somehow related to the shrine’s main gods, while the massha enshrine a deity that is not relevant to the shrine’s main god; however, sessya and massha are not always strictly differentiated anymore.

More on Shinto Shrines

Omikuji [おみくじ]

A popular thing to do at a shrine is omikuji, or fortune telling. The omikuji tells you how lucky you are, which varies from the very ominous daikyou [大凶] to the super lucky daikichi [大吉]. The omikuji also goes into detail about what kinds of events may happen in the near future and what you should be wary of. You can tie the omikuji to a tree in the shrine, or take it home as a message from the gods.

Omamori [お守り]

An omamori is essentially a good luck charm that a shrine sells. There are a wide variety of charms and some shrines specialize, or are popular, for a particular type of charm, i.e. Tenmangu shrines have lots of charms to help you study or pass an exam.

Ema [絵馬]

Ema are small wooden boards on which you write your wishes in hopes that the gods with grant them. You may notice that the kanji of ema bares the character for horse. In ancient times people would often give a horse to a shrine as an offering. But after Heian Period, people started donating paper, wooden, or clay horses to the shrine instead. It wasn’t until the Edo Period that people started writing down their wishes on small wooden boards.

When you are writing your wishes on the ema, be sure to include your name (it doesn’t have to be all of it) and hang it in the shrine in the specified area.

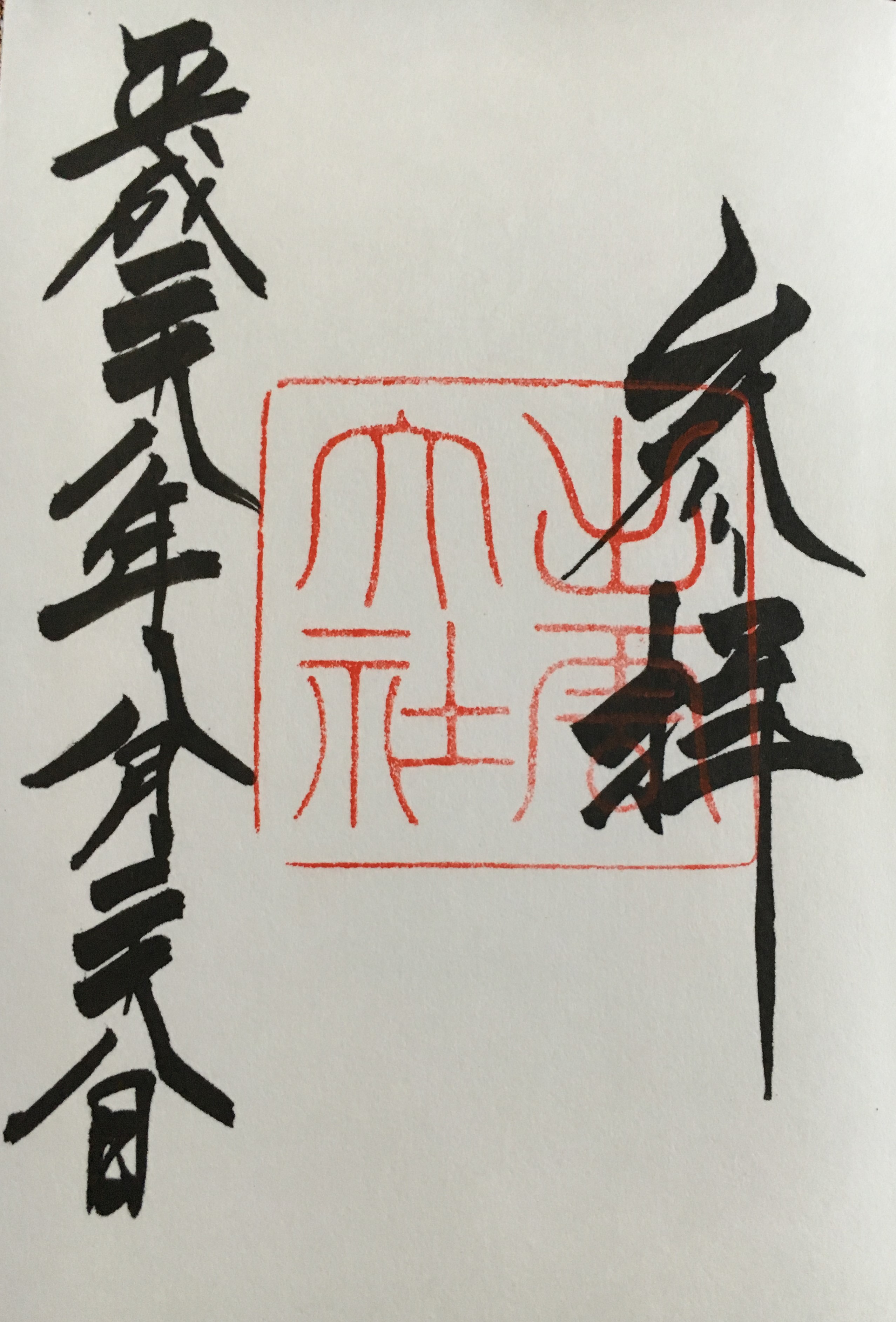

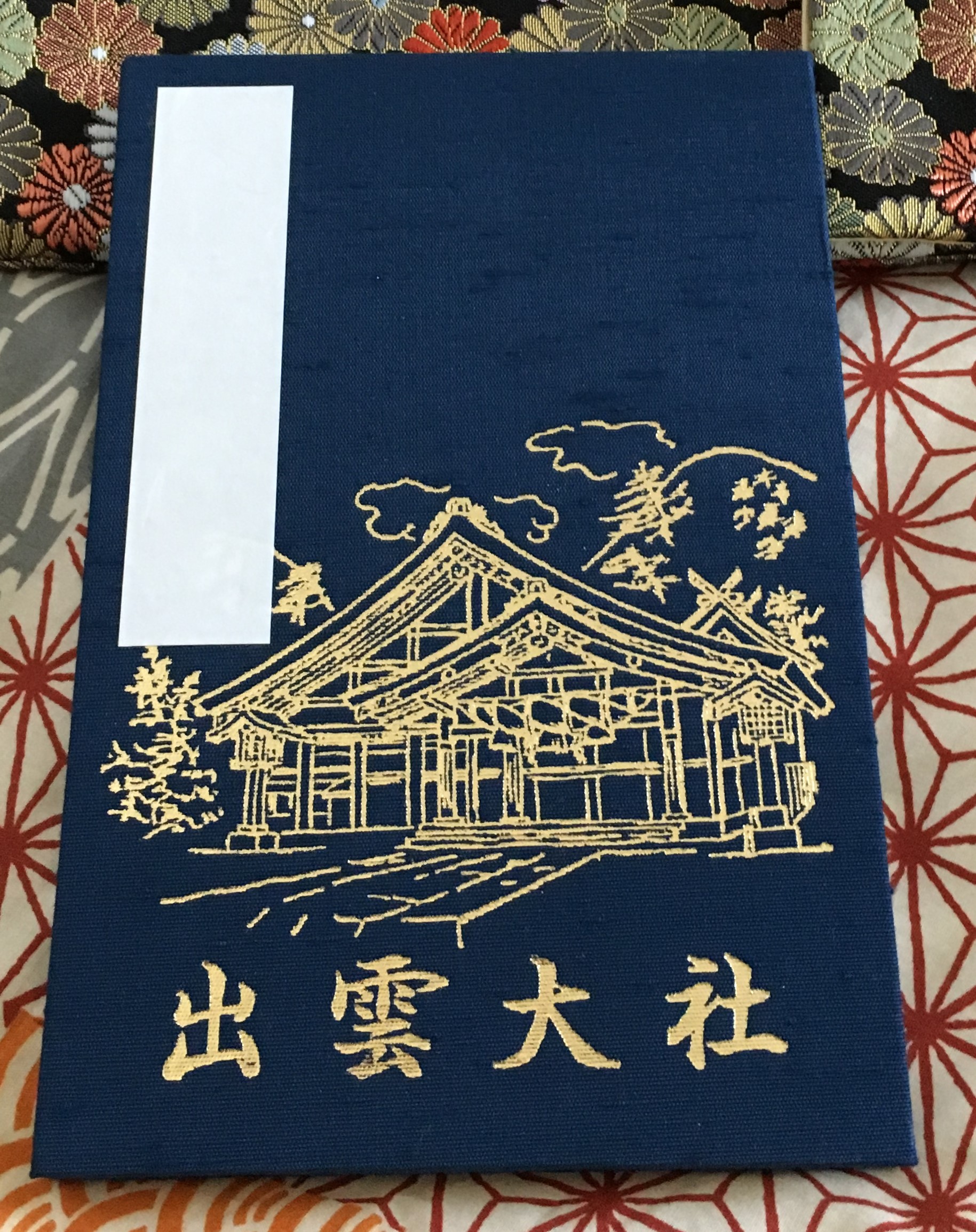

Shuin [朱印]

A shuin is a shrine or temple’s special “signature”. Originating as proof that someone had visited one the 33 Kwando Temples, shrines eventually adopted this practice as well.

To get a shuin, you will first need to get a shuinchou [朱印帳], which is special book made for shuin—sort of like an autograph book. There are many places you can get a shuinchou. For example, big shrines or temples often sell their own shuinchou, but you can also find them in souvenir stores or even online. Both shuin and shuinchou can be really elaborate and are really fun to collect. They are a great way to reminisce and document all the shrines and temples you visit. I really encourage them.

Leave a Reply